Did you wonder why a de Havilland biplane featured as a centrepiece in the centenary celebration for the Woodford Aerodrome at the Avro Heritage Museum on 17 September 2024 or why that particular aeroplane which had emerged as the winner of an aeroplane design competition in which it didn’t even participate became so significant for not only the Avro company but also the Lancashire Aero Club?

Until WW1 Avro made limited use of a small airfield that had been created at Trafford Park, but most of their aircraft were still built in sections and transported to Manchester’s London Road (now Piccadilly) railway station for delivery to Brooklands near London for assembly.

Aircraft built at the Crossley Motor managed National Aircraft Factory (NAF) No.2 at Heaton Chapel near Stockport were similarly transported to Aircraft Depots nearer to the point of delivery rather than fly them from the Cringle Fields airstrip adjacent to their factory. This was the same for many of the factories around the UK, many of whom sent their military aircraft to Farnborough for assembly and testing by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC).

The massive expansion of the RFC meant they couldn’t cope with the increased workload and so Air Acceptance Parks (AAP) were established nearer to areas of aircraft production. During 1918 Air Acceptance Park No.15 was created on land on the Chorlton Didsbury border on what is now Hough End Sports Field. The airfield had six large and six medium sized hangars and a 3500 ft runway. As the nearest train station was Alexandra Park, the airfield became known as Alexandra Park, even though there was (and still exists) an Alexandra Park less than a mile away.

Aircraft production at the National Aircraft Factory No.2 stopped in 1919, and Crossley’s returned to car and bus production. Avro continued to use Alexandra Park despite having few orders for new aircraft. In order to retain their workforce, they diversified and made bathtubs, pool tables and even designed and built their own car. By 1920 Crossley were concerned about the potential competition of Avro cars and so took a majority 70% stake in Avro which retained the Avro name. This halted Avro car production and Avro were used to manufacture Crossley motor bodies alongside their aircraft production which continued to be flown from Alexandra Park.

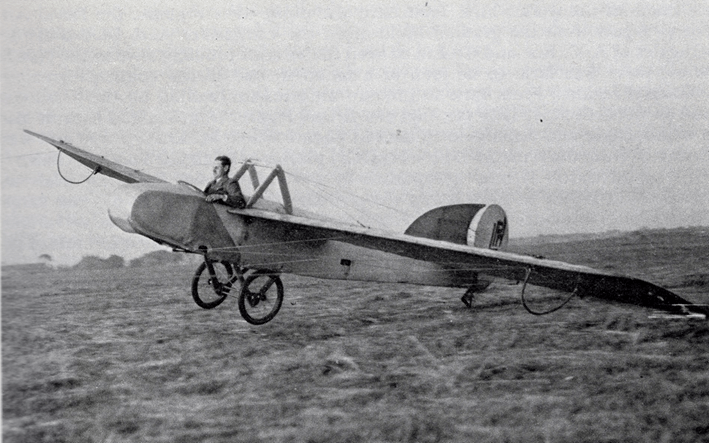

John Leeming from Chorlton-cum-Hardy who had unsuccessfully built model gliders prior to WW1 was encouraged by reports of German glider pilots so he set out to design his own glider which could be dismantled and stored in a garage. He was allowed to use parts from the Avro scrap heap and surplus stores and together with two colleagues Tom Prince and Clement Wood built a glider they designated the LPW. As more and more people got involved the Lancashire Flying Club was formed to organise their activities. However, they realised that there were many ‘flying clubs’, but most were associated with pigeon racing. So in 1922 the name was changed, using the name of an organisation that had briefly existed in 1909, to the Lancashire Aero Club. Soon after they moved their activities to Alexandra Park. The LPW glider made its first flight on 24 May 1924 towed into the air at the end of a long rope attached to a car. It made several flights of “about six feet above the ground of perhaps a hundred yards or more”.

Following WW1 Alexandra Park had become Manchester’s first proper airport with Daimler Airways flying daily services to Croydon Airport near London and Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam. However, all services from Manchester were terminated in April 1924 when Daimler Airways merged with several other airlines into Imperial Airways.

Unfortunately, the terms of the lease of Alexndra Park laid down by owner Lord Egerton of Tatton stipulated that flying would cease within five years of the end of WW1. The land would return for recreational use and for the building of houses. The airfield officially closed on 24 August 1924, but Alliot Verdon-Roe had already identified land at New Hall Farm, Woodford near Poynton.

On 17 September 1924 the land at Woodford was officially purchased. The area needed much work including levelling, draining, compacting the ground, removal of ponds, and erecting fences, and so the preparation of the site suitable for an airfield proceeded slowly.

After the closure of Alexandra Park Airfield two of the hangars being demolished were purchased by Avro for use at Woodford. Work began on erecting the first hangar but a severe storm in the winter of 1924/5 caused it to collapse. Some parts were salvaged and combined with parts from the second, un-erected hangar, to build a single replacement which was known as Hangar 1.

Following the completion of Hangar 1, it was clear that additional hangar space was required. Avro erected an ex-WW1 Bessoneau canvas hangar (known as the ‘Tent’), which was used as a temporary and movable hangar at the airfield.

The homeless Lancashire Aero Club were invited to move to Woodford with Avro. An engine was attached to the LPW, but it was too heavy and never got off the ground, so it was used for taxiing and ground handling experience until eventually abandoned and then scrapped.

By the middle of 1924 the Air Ministry had invited aircraft manufacturers to design and fly an affordable light aeroplane suitable for private aero clubs. Trials were held at Lympne in Kent in order to determine the most suitable aircraft that could be then donated to five selected flying clubs around the UK.

The 1924 trial, officially called the ‘Two-Seater Dual Control Light Aeroplane Competition’ was held from 27 September to 4 October 1924. Competing aircraft had to have engines of no more than 1,100 cc, to have full dual controls, and one or two airspeed indicators visible from either cockpit.

The elimination trials, held on Sunday 28 September were not expected to be as challenging as they turned out to be. There was a transport, store and reassemble test which involved folding or dismantling the wings, moving the aircraft a short distance and housing in a shed 10 ft wide which had to be completed by no more than two people. A flying test followed which required a flight of one lap plus a figure of eight to be made from each cockpit in turn.

The flying competition started on Monday 29 September with points awarded on performance of four different tests:

1. high speed

2. low speed

3. distance required to take off and clear an obstacle

4. length of landing run

The total time in the air during the competition was also logged.

The Air Ministry offered a £2,000 prize for the winner, £1,000 for the runner-up and there was a £500 prize for the best combined take-off and landing performance with £100 for the runner-up and a £300 reliability prize from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and the British Cycle and Motor-cycle Manufacturers’ and Traders’ Union, awarded to the aircraft that flew the most laps during the week.

For the 1924 trials there were 19 entries.

Only eight entrants survived the elimination tests to take part in the actual trials. The high dropout was considered to have been due to underdeveloped engines and insufficient time to prepare the airframes.

The successful machines were numbers 1, 3, 4, 5, 14, 15, 18 and 19. Pixies No.s 17 and 18 were the same aircraft, configurable as either a monoplane or a biplane, but only flown as No.18 in monoplane configuration. This dropped out of the trials on Tuesday 30 September, leaving only seven aircraft to end with officially recognised performances.

The Air Ministry first prize was won by Maurice Piercey flying the Beardmore “Wee Bee” (No. 4). The runner up was the Bristol Brownie (No. 1). These were the only two aircraft reliable enough to complete the high-speed tests. They reached 70.1 mph and 65.2 mph respectively. The Brownie also won the £500 take-off and landing prize, with the Cygnet II (No.15) running up. The Cranwell CLA.2 (No.3) went the furthest and flew for longest to win the £300 reliability prize. It covered 762.5 miles after almost 18 hours flying.

Although there was some concern the poor results were because the manufacturers had not been allowed enough time to develop their designs the Air Ministry regarded that “valuable results had been achieved”.

However, in reality the trials had not produced an aeroplane that was suitable for civilian flying clubs, and the five flying clubs of which the Lancashire Aero Club was one were impatient to receive the aeroplanes that had been promised to them.

The de Havilland aeroplane company had not sent an aeroplane to trials as they considered the regulations for entry precluded the construction of a suitable machine. By November 1924 de Havilland were working on a design based on their DH.51 biplane. The new smaller aeroplane was designated the DH.60 and named the Moth. It was a two seat, fabric covered biplane with wings that folded back for easy storage. It was fitted with a 60hp Cirrus engine, and so is often referred as the DH.60 Cirrus Moth.

The prototype G-EBKT made its maiden flight on 22 February 1925 from the de Havilland works airfield at Stag Lane flown by Geoffrey de Havilland. It was a sturdy, light aeroplane with good handling characteristics that could take off quickly and land slowly making a suitable training aircraft for civilian aeroclubs.

The Air Ministry invited the aeroclubs to Stag Lane to review the Cirrus Moth. John Leeming as Chairman went on behalf of Lancashire Aero Club, and as with all the representatives from the other aeroclubs, was hugely impressed and desperate to get their own. This created a dilemma for the Air Ministry as they had held a competition which several aircraft manufacturers had spent a lot of time, money and effort in creating an aeroplane that was unsuitable whilst de Havilland which hadn’t entered the competition but had created the aircraft of choice.

It’s not documented on how this was resolved but on 16 April 1925 it was announced that the government would order two Cirrus Moths and a spare engine for the Lancashire, London, Newcastle, Midland, and Yorkshire Aero Clubs. However, there was some concern that the aeroplanes may be handed over to amateurs with no flying experience, so as part of the deal each club had to employ at least one qualified ground engine who could certify the aeroplane and two trained pilot instructors (who the government would sponsor the training of).

By the middle of 1925 Lancashire Aero Club were progressing well. They had moved to Avro’s Woodford aerodrome, allocated hangar space and whilst preparation of the airfield continued, they overcame a mountain of teething issues as they eagerly awaited delivery of their two Cirrus Moths.

Lancashire Aero Club’s first Cirrus Moth G-EBLR was due to be delivered on Sunday 28 June 1925. It was decided that John Leeming would travel to de Havilland’s facility at Stag Lane and fly back with a de Havilland pilot to Woodford where a huge reception was laid on for 7 o’clock in the evening with a large crowd expected.

Leeming arrived at Stag Lane in the morning only to be told that the aircraft had developed engine trouble which would need to be thoroughly investigated. The story is continued by John Leeming (courtesy of Lancashire Aero Club).

“All through the afternoon the mechanics searched, I waited anxiously. I knew that far away in Manchester, as seven o’clock drew near, people would be streaming out towards Woodford to see the first appearance in public of the much talked of Lancashire Aero Club. The closing down of Alexandra Park and the various delays in the Air Ministry scheme had caused a number of people to become suspicious. If for any reason we now failed to arrive as advertised, I had no illusions as to what would happen. We were not strong enough to take such a setback; it would be the end of the Lancashire Club, for ridicule would kill it.

de Havilland had no other machine that they could send. There were only three Moths in existence at the time and their own test Moth G-EBKT had gone that morning to Coventry. It was uncertain when this would be back, and the uncertainty continued as the afternoon dragged on.

At five o’clock, two hours before we were due at Woodford, the mechanics discovered the trouble. It was serious; it would take two days to put right. The fields of Edgeware rang with my lamentations. To telegraph Woodford that I could not keep the appointment as arranged meant the failure of all our work. Almost weeping, and certainly swearing most wickedly, I implored the gods to avert this disaster.

St.Barbe, de Havilland’s sales manager spoke assurances of a delivery within a couple of days at the most. I refused to be comforted; what they couldn’t understand was the harm even one day’s delay was going to cause. At 5.25, just as had accepted the inevitable and was about to wire to Woodford, an aeroplane roared over Stag Lane.

‘There’s one!’ I shouted. ‘Get him down! Make him go with me!’

Broad, a de Havilland pilot peered at the machine that was coming into land. ‘It’s KT’ he said suddenly. ‘It’s Cobham back’.

We did some very hurried talking and arranging during the next few minutes. If KT was not our proper machine it was at least a Moth. Probably few at Woodford would realise that a change had been made. Once more bluff might save the situation. If KT was flown there, formally accepted, and then flown back again the next day, our own Moth could be delivered without fuss as soon as it was ready.

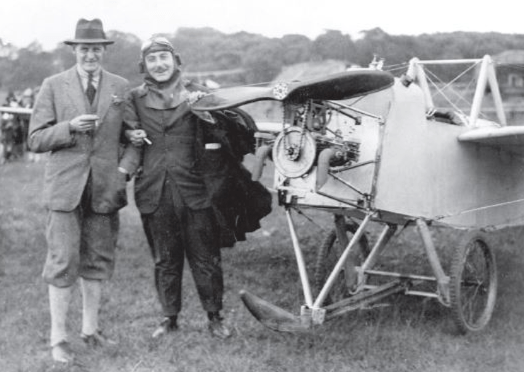

St.Barbe explained the situation to the pilot who had just landed and introduced me to him. ‘You’ll have heard of him I expect’ he said. ‘He flew Air Minister Brancker to India, and he’s going to try a long-distance flight. Alan Cobham’s his name.’

Cobham was tired after a double journey to Coventry and back, and a busy day there arranging an engine for his proposed lang-distance flight. But as soon as he understood the position he agreed to fly to Woodford.

We landed at Woodford at 7.30 in the evening, after and uneventful flight in perfect weather. There was quite a large crowd to see the first Moth arrive.

Only Tom Prince gave any trouble. ‘Have you signed for this machine?’ he demanded. I nodded. ‘Then we’ve been done. I knew it would happen. They’ve framed us, they’ve palmed off an old machine on you. I tell you it’s one painted up. It’s been used and –‘

‘Hush’ I implored. ‘I’ll explain later.’

‘It’s not new!’ he shouted. ‘We mustn’t take delivery. I’ll talk to that pilot!’

I managed to hush him in the end, and the next day the local press reported and applauded the safe arrival of the club’s first Moth. The same day Cobham, after returning the pyjamas and razor I had lent him, flew the machine back to Stag Lane.

That evening my telephone rang, and at the other end was a much concerned and very worried member of the club.

‘I went down,’ he stuttered, ‘thought I’d just have another look at it, and the Moth’s gone! It’s gone! Just isn’t there! The farmer says two men came about eleven o’clock this morning and one of them flew it away.’

I was reluctant to explain the matter fully. The editor of a certain newspaper happened to be visiting us that evening and was sitting within a yard of the telephone. I tried guarded hints and vague assurances.

‘But it’s gone!’ the member kept repeating. ‘Aren’t you going to get the police?’ My refusal lost me forever the respect and support of that member. He was never quite the same with me again’.”

The first of Lancashire Aero Clubs Cirrus Moths register G-EBLR was finally delivered on Tuesday 21 July flown by Alan Cobham.

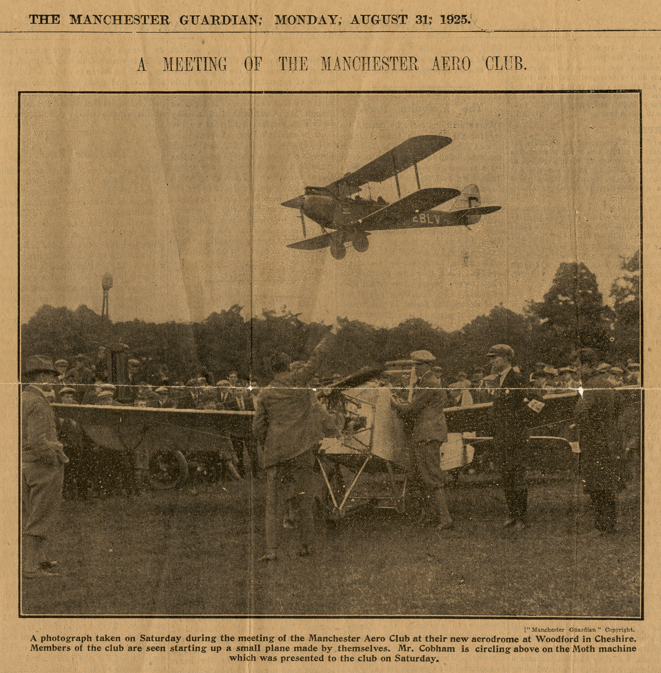

Their second G-EBLV was also delivered to Woodford by Alan Cobham. It arrived on Saturday 29 August 1925 at 3pm and was celebrated by an event to which the public were invited to watch a flying display (Woodford’s first Air Display?) and for dignitaries to have joy rides. The LPW glider was still there and “careered about the aerodrome under its own power – until the magneto ceased to function. Early in the afternoon a wheel came off one of the Moths while it was in the air; on landing, this machine was carried quickly into the hangar, and about teatime the engine of the second Moth developed valve trouble but fortunately, Bert Hinkler was at Woodford with an Avro 504N.”

DH Cirrus Moth G-EBKT was written off (damaged beyond repair) 21 August 1927 after a crash at Stanmore near London, however its propeller is on display in the reception of the former de Havilland propeller factory, now the UK headquarters MBDA in Bolton. The rudder is believed to have been used as part of damage repair to DH Cirrus Moth G-EBLV.

DH Cirrus Moth G-EBLR was written off on 11 June 1927. after on a training flight from Woodford when the engine failed. The aircraft force landed at Hale, Cheshire. The aircraft hit an iron fence and came to rest injuring both occupants, but the aircraft was damaged beyond repair.

DH Cirrus Moth G-EBLV was formerly operated by BAe and is now with the Shuttleworth Trust in Bedfordshire. It has made frequent visits back to Woodford and Lancashire Aero Club’s base at Barton, most notably for the 70th anniversary of Lancashire Aero Club in 1992. It was therefore and absolute necessity on the 17th September 2024 to display, this historic aircraft which is so important in the history of both Avro at Woodford and Lancashire Aero Club albeit as a static in front of a Lancashire Aero Club gazebo to commemorate the centenary of the A V Roe company acquiring the Woodford site.

With thanks to:

Cliff Mort and Lancashire Aero Club

Ernest Hart

and

Mick Crossley – MBDA UK Ltd.

Even though I was not looking for it and don’t know how or why I received it, as a former Woodford resident, I thoroughly enjoyed this piece of history. Thanks for posting

LikeLike

Well researched and very interesting piece of history. Nice one, Frank!

LikeLike